SF Bay Guardian,

February 16, 2000

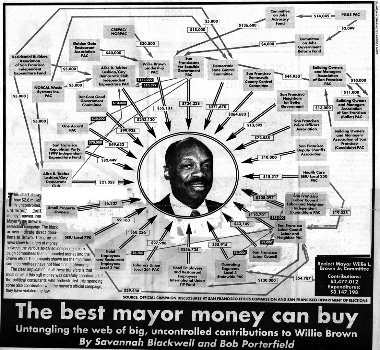

The Best Mayor

Money Can Buy

Untangling the web of big, uncontrolled contributions to Willie Brown

By Savannah Blackwell and Bob Porterfield

When U.S. district judge Claudia Wilken struck down the 20-year-old San Francisco law limiting the amount of money special interests could contribute to political action and other independent expenditure committees last fall, she drastically changed the complexion of local — and possibly national — politics.

The ruling received little media attention, but it was the stuff of big-money, special interest dreams. Wilken made it possible for companies with city contracts or pending projects to pour tens of thousands of dollars into Mayor Willie Brown's reelection campaign — with no controls or limits.

The upshot: Brown's campaign set a new standard for political sleaze.

A Bay Guardian analysis of the most recent "soft money" spending reports shows:

- Unregulated soft money accounted for nearly half of the unprecedented $5.78 million that went for Brown's reelection (see chart, above).

- Much of that money came in chunks of $5,000 to $95,000 from companies, individuals, and lobbying groups that regularly do business with the city or have projects or contracts pending before city agencies (see box, page 28).

- The mind-boggling flow of money back and forth between some 22 supposedly independent committees and PACs that played a major role in Brown's reelection suggests strongly that the effort was carefully coordinated through political consultants with close ties to the mayor. If Brown, or any officials on his campaign staff, were involved in the coordination, it would be a violation of law.

- Among the donor groups was a PAC called "One Accord" that is based at the home of a member of the Board of Appeals; that PAC accepted a $20,000 donation from developer Joe O'Donoghue, whose Residential Builders Association members regularly have business before the board.

Campaign reform advocates say that this election set a frightening precedent and that if this type of uncontrolled spending is allowed to continue, it will rewrite the entire political playbook in California and perhaps the nation.

Money talks

Laws limiting the amount of money a single donor can give to a candidate are designed to prevent any one contributor from having too much influence over a political candidate. But Wilken's decision — in a lawsuit filed by Brown's allies and argued by a lawyer who has also worked for Brown -- made it possible for companies and lobbyists who need the mayor's support to give him so much money he cannot help but be indebted to them.

“[The donors to committees supporting Brown] are generally entities that have a financial stake in the decisions in the City and County of San Francisco,” Jim Knox, executive director of California Common Cause, told the Bay Guardian.

For example, the city’s Planning and Redevelopment Commissions, whose members are all appointed by the mayor, decided Jan. 13 that the site of a future Bloomingdale’s should be annexed to an existing redevelopment area. That means the developer, Forest City Development, which contributed a total of $66,500 in soft money (including donations from executives and affiliates) to groups supporting the mayor’s reelection, is eligible for a city property tax rebate. Forest City is also seeking $30 million from the city in tax-increment financing (see “Blooming Disaster,” 2/3/99).

Political observers told the Bay Guardian they expect the three individuals largely responsible for spear-heading Brown’s soft-money campaign, consultants Robert Barnes, Mark Mosher, and John Whitehurst, to use the same tactic to help the local Democratic Party machine as well as business and real estate interests push candidates in district elections, coming up in November. Barnes has worked for Brown ally Natalie Berg; Mosher’s employers have poured large sums of money into Brown’s campaign.

“It’s not clear that anything can be done in time for November,” Knox told the Bay Guardian. “But we are spearheading a move to put an initiative on the ballot which would institute public financing of campaigns as a way to drive out reliance on independent expenditures.”

Officials from Common Cause plan to be present at a Feb. 16 hearing to review Brown’s soft-money campaign. Sup. Tom Ammiano, who ran against Brown, called for the hearing.

Attacking Ammiano

San Franciscans for Sensible Government, a group founded by business organizations in the city and whose vice president, Mosher, has long worked as a staffer to the Committee on Jobs -– which represents the city’s biggest employers -– filed the suit last May. Joseph Remcho, a lawyer who has represented Brown, represented the group in its suit.

Court documents make it clear that the group filed the suit in an effort to find a way to raise unlimited dollars to help Brown win reelection. In his declaration to the court, Mosher complained that because the group had to collect money in $500 chunks, it could not put out as much anti-Ammiano rhetoric as it had wanted in the 1998 race for election to the Board of Supervisors. Ammiano secured the board presidency in that election.

“As a result of the limits on contributions imposed by the Ordinance, and the San Francisco City Attorney’s interpretation of the Ordinance, SFSG PAC’s ability to communicate with voters about Supervisor Ammiano’s record was significantly hindered,” Mosher stated in his declaration to the court. “SFSG PAC could not pursue its plan for billboard or newspaper advertisements due to its inability to raise contributions sufficient to support the cost of such communications.”

The filing of the suit received little media attention, and City Attorney Louise Renne’s office did nothing to seek publicity for the case or to gain support for the city’s position.

“If the city attorney had contacted us, we could have retained a lawyer to work with the city attorney to protect the law,” Clint Reilly, a millionaire political consultant who ran against Brown, told the Bay Guardian.

The City Attorney’s Office is appealing Wilken’s decision, which was upheld Oct. 20 by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The U.S. Supreme Court recently ruled that limits on contributions going directly to candidates are constitutional.

By the numbers

Of the total $5,787,310 so far reported as being spent to reelect Brown, about $2,640,112 -- nearly 46 percent -- was soft money. And much of that came in big chunks. Although the mayor needed contributions from almost 7,000 individuals and businesses (who could give only $750 each) to raise roughly $3 million for his official campaign, it took only 143 individuals and PACs to raise $1.7 million of the soft-money total.

Included in this deluge of money were 58 contributions of $5,000; 25 contributions of $10,000; 12 contributions of $15,000; 11 contributions of $25,000; 3 contributions of $30,000; 2 contributions of $35,000; 2 contributions of $50,000; 1 contribution of $75,000; and 1 of $95,000. In between were 28 other contributions ranging from $6,000 to $20,000 apiece. Scores more special interest contributors ponied up $1,000 to $4,000 each.

Other than expenditures by organized labor, the lion’s share of soft money that fueled Brown’s campaign came from landlords, real estate developers, and builders who face issues ranging from rent control to gentrification. Some have major projects pending before the city (see box).

Donald Fisher, founder of the Gap, contributed $120,090 in soft money through a number of his companies, including a $75,000 contribution to the San Franciscans for Sensible Government PAC.

Stein Kingsley Stein, a developer of SoMa office space, provided $105,000 in soft-money contributions and another $1,000 directly to Brown’s committee, while the company’s lobbyists, Robert McCarthy and Debra Stein (no relation to company principals), made $21,600 in contributions to PACs supporting the mayor.

Ron Kaufman, husband of Sup. Barbara Kaufman, who owns several downtown office buildings, weighed in with $5,000 in contributions made by several of his individual committees.

Victor Makras, a Realtor and a member of the city Public Utilities commission, gave $13,000. Soon after joining the PUC, Makras actively supported the awarding of a lucrative golf course management contract to a group headed by one of Brown’s former legislative employees.

Jaidin Consulting Group, a company owned in part by Walter Wong, a self-styled permit “expediter” who is something of a permanent fixture behind the counter at the city’s Planning Department, contributed $15,000 to the Alice B. Toklas Lesbian/Gay Democratic Club. City records show that Jaidin currently has a $95,000 no-bid contract to provide public relations services to the Department of Building Inspection.

The Sangiacomo family businesses, which include Sunset Scavenger Company, provided $54,425 in soft money and another $27,875 in direct contributions to Brown’s committee. Sunset Scavenger has at least $4.7 million in city contracts.

P.S. “Mushroom” PACs, or those formed literally overnight to jump on Brown’s campaign money-go-round, weren’t limited to the big boys downtown.

An example is the One Accord PAC, formed less than one week after the November general election by Debra Drooh, a clerk working the midnight shift in the San Francisco trial courts. The PAC’s office address is the residence of Sabrina Saunders, for the past 14 months a member of the city’s Board of Appeals and a member of the San Francisco Democratic County Central Committee.

Within six weeks this upstart PAC collected nearly $65,000 -- most of it from business and development interests. The major contributors were San Franciscans for Sensible Government, with $30,000; Residential Builders Association head Joe O’Donoghue, who made a personal contribution of $25,000; and Johnny Brennan, a local builder, who threw in $5,000. RBA projects frequently come before the Board of Appeals.

Although Drooh claimed in her official PAC filing that One Accord was formed to support “state and local candidates and ballot measures,” a review of the committee’s $64,544 in expenditures through Dec. 31 suggests the bulk of the money benefited Brown’s runoff campaign. Saunders, along with the majority of members of the Board of Appeals, voted Feb. 9 to uphold the Planning Commission’s approval of a 16-unit loft complex to be built next door to the San Francisco Food Bank’s warehouse, on Pennsylvania and 23rd Streets.

Drooh could not be reached for comment. Saunders, contacted Monday at the PAC’s office phone number, said she was tied up on another call and asked the Bay Guardian to call back in an hour. Nobody answered the phone.

BOX ACCOMPANYING THIS STORY:

_________________________________________________________________

Big donors with projects pending before city agencies*

Donald Fisher interests** ($120,090)

Development projects on Harrison Street pending before city officials

Stein Kingsley Stein (SKS) ($105,000)

Developers of several SoMa live-work projects before various city agencies

Forest City ($66,500)

Proposed Bloomingdale's and hotel project before city officials

Ronald Kaufman interests ($50,000)

Husband of Sup. Barbara Kaufman; office project on 17th and Rhose Island Streets pending before city officials

Montgomery Watson ($49,000)

Holds more than $6 million in contracts with the city's Public Utilities Commission

Michael Joseph O'Donoghue ($30,000)

Advocates for the Residential Builders Association, whose members have dozens of live-work projects pending before city officials

* TOTAL AGGREGATE CONTRIBUTIONS TO ALL PACs

** "INTERESTS" INCLUDES AFFILIATED BUSINESSES