San Francisco Bay Guardian - July 5, 2000

NO CASH, NO CONTRACT

How Ernie Meriweather’s plan to create jobs for troubled kids collapsed when he wouldn't fork over a mysterious $60,000 cash payment.

By Savannah Blackwell

In 1994, when African American community activist Ernie Meriweather first conceived an ambitious development project on the San Francisco waterfront that would create jobs for troubled youth, he knew there would be obstacles.

For starters, he'd never done any real estate development work, and certainly nothing of this scale. His idea would cost hundreds of millions of dollars – and he had no personal connections to any deep-pocketed financiers. And although Sups. Tom Ammiano and Sue Bierman had encouraged him to pursue his plan for Pier 30- 32, navigating the city’s bureaucracy would be tough.

But he never expected to learn that he needed to clear an unofficial hurdle – coming up with a suspicious $60,000 cash payment, which a city official told him was necessary to get the blessing of Mayor Willie Brown.

Meriweather, who had campaigned for Brown in 1995 and had high hopes for the city’s first African American mayor, was baffled. He’d worked with city officials on small projects during the years when Art Agnos and Frank Jordan were mayor, but he’d never been asked to pay what sounded to him like a bribe. Smelling trouble, he never paid the $60,000 that he was told would give him the inside line on the right to develop a prime piece of Port of San Francisco property. As a result, he believes, his plan never moved forward with city officials.

Instead the deal went to a competitor who had all the right political connections: a consortium including the Port of Singapore and the founder of a Taiwan-based maritime shipping company won the exclusive right to negotiate the development of Pier 30-32. The team’s victory appears to have been based at least in part on political influence and backroom dealing by one of city hall’s most powerful lobbyists – Marcia Smolens – and another key member of the Democratic Party political machine, state senator John Burton.

The project that the big out-of-town corporate group wants to build contains key elements of Meriweather’s original proposal, according to Meriweather and other members of the Embarcadero Cultural Center International (ECCI), the team he put together to develop the proposal.

“We had wanted to do something to provide an opportunity for people who work on jobs that don’t make enough money to pay the rent,” Meriweather said. “But what happened just shows you why the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. And worse. Its about corruption, which I’ve learned you have to fight regardless of who practices it.”

The story of what happened to Meriweather’s dream is startling not because the project failed (all sorts of grand ideas like this never move past paper budgets and designs) or because it involves a powerful ally of Brown’s soliciting a fee to get a project approved (powerful local lobbyists, for instance, use their connections to the mayor as grounds for charging their clients big lobbying fees).

What’s extraordinary is that Meriweather and two other people involved in the project (a prominent architect and a source who asked not to be identified) insist that Meriweather’s team was asked to pay a bribe that, they understood, would go to the mayor to win his approval for their project.

Meriweather and the members of his team who spoke to the Bay Guardian for this article say that the group was asked to come up with the money – in cash – on numerous occasions by a person who was among Brown’s closest friends and allies.

That person, then-Recreation and Park commissioner Rotea Gilford, died March 14, 1998, so it’s impossible to know how he would explain his involvement with the project.

Meriweather says he met with Gilford more than a dozen times – at the Southeast Community College campus, at Gilford’s house, at his City Hall office, and later, in the ailing Gilford’s hospital room – and Gilford consistently told him that if he wanted the project to succeed, he needed to come up with $60,000 to “get the wheels turning.”

One of Meriweather’s partners recalls Gilford demanding the money in front of ECCI members at a gathering at Gilford’s home in the Lower Haight. Gilford made it very clear, Meriweather and his partner say, that the money was not a traditional consulting fee, which Gilford would have kept. The money, they say, was to go to “higher-ups” who could pull strings. In fact, Meriweather says he was told repeatedly that it would go to “the boss,” Willie Brown.

Minutes from ECCI meetings going back to April 1996 contain repeated mentions of the $60,000 payment. It is described in those minutes as a “consulting fee,” because, Meriweather says, the group didn’t know how else to describe it.

There is no proof that Brown ever knew about the alleged bribe. We have no evidence suggesting that the eventual winning bidder did anything illegal. It’s entirely possible that Meriweather, a relative novice at city politics, misunderstood the exact purpose of the $60,000 request – although he insists it was never described to him as anything other than a payoff.

But it’s hard to doubt Meriweather’s veracity or motives: he has nothing to gain and much to lose by coming forward with this story, which could seriously damage his business and personal relationships in the pro-Brown camps of the black community. And his story is confirmed by others and by company records.

Regardless, Meriweather’s case – which also involves infamous political players such as Charlie Walker and Eddie DeBartolo – exemplifies a city government awash in corruption. His story, coming amid FBI investigations of Brown’s administration, shows a city hall where insider politics trumps not only good intentions but also the rules of the game – and where sometimes, you have to pay to play.

As much as anything else, this is a story about what happens when an ordinary citizen with great ideas but few connections tries to do business in todays San Francisco.

For Mayor Brown’s full response, see “A Word from the Mayor,” in box above.

Jobs for Kids

Meriweather hails from Augusta, Ga. One of three children, he is the son of minister for the Seventh Day Adventists. He grew up poor and in 1950 joined the army. When he got out in 1959, he moved to Long Beach and worked at Douglas Aircraft as a technician.

During the mid '70s he worked for a nonprofit organization that secured jobs for young people who had run into trouble. In 1976 he moved to San Francisco and continued to work as a job-placement counselor, mostly trying to get at-risk kids off the streets, out of trouble, and into jobs.

In 1987, with a little start-up money from his wife's family, he launched a project called We the People, which produced TV shows to encourage activism in the African American community. The show We the People airs on public access channel 29 at 8 p.m. on the first and second Tuesday of the month.

In the early 1990s Meriweather started interviewing young people in jail, and he kept hearing the same complaint. They had wound up in crime, they said, because there weren't any jobs.

That's hardly a revelation, but Meriweather, who has never lost his idealism or his exuberance, decided to commit himself to creating jobs for troubled youth.

He came up with the idea of building a project on the San Francisco waterfront that would combine restaurants, shops, and maritime uses – and would employ local kids. It was an ambitious idea, the sort a lot of people would consider unrealistic, but Meriweather went ahead anyway. He set his sights on Pier 38, but another developer got the contract.

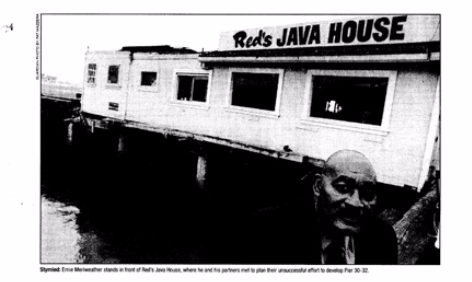

Ammiano and Bierman then suggested he look elsewhere on the waterfront, and he wound up focusing on Pier 30-32. Situated in the South Beach waterfront area, between Brannan and Bryant Streets on the Embarcadero, Pier 30-32 is a huge parking lot. Red's Java House perches next to it, as it has since the 1940s.

"I remember [Meriweather's] idea had a maritime emphasis," Ammiano told us. "I remember talking to him and that his idea had great merit but was pushed aside."

Bierman, too, encouraged Meriweather to stick with the project. "The Port Director informs me that your [Pier 38] proposal may be appropriate for future development at another location," Bierman wrote in a 1996 letter to Meriweather.

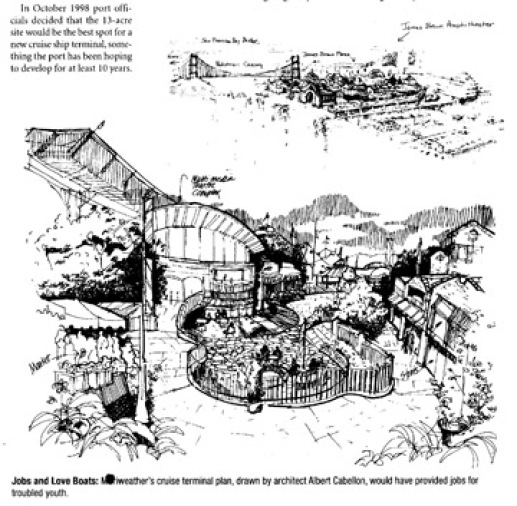

In October 1998 port officials decided that the 13-acre site would be the best spot for a new cruise ship terminal, something the port has been hoping to develop for at least 10 years.

The port's 1997 Waterfront Land Use Plan describes Pier 30-32 and the adjacent lot as "the Port's largest development site," appropriate for the terminal and a mix of commercial and public entertainment-oriented enterprises.

During the next several years, more than $1 billion worth of construction is expected to transform to the port. The cruise terminal project at Pier 30-32, the Chelsea Piers, and the remodeling of the Ferry Building are the biggest projects.

The cruise terminal is a big part of the waterfront's future: the port expects at least a 70 percent increase in the number of cruise ships passengers by 2003, according to a September 1998 report by the port's planning and development director, Paul Osmundson. That October he recommended Pier 30-32 for the cruise terminal and suggested that a hotel with retail outlets be built on the adjacent lot. The Port Commission agreed.

Meriweather figured that was ideal. He had long since assembled a development team and drawn up an impressive plan that featured a cruise terminal. It also included a hotel, a movie theater and outdoor amphitheater – named after the godfather of soul, James Brown – 15 to 20 shops, a conference center, a fruit and vegetable market, a museum, and a child care center.

Former port commissioner and labor leader James Herman, who died in 1998, encouraged him in the idea, Meriweather says. Port officials decided to memorialize Herman by naming the cruise terminal after him.

Meriweather had been going to Port Commission meetings regularly since 1996, asking to get the development rights. He and his ECCI team had presented a proposal for Pier 30-32 as early as September 1997.

"It seemed like he came to every meeting," a source who formerly worked at the port remarked. "He was always there."

Meriweather and his group met regularly at the Java House. Group members included Col. Lincoln Langley, who had maritime experience and whom Meriweather had known for many years, and an architect named Albert Cabellon, who had worked on high-end resort developments and is president of a design/build firm based in Burlingame. Cabellon was to script a budget and visuals for the project.

Meriweather then met with merchants and community groups to generate support for the project. He approached the Delancey Street Foundation's Mimi Silbert, staffers at the Ella Hill Hutch Community Center, and a host of other organizations. He also went to city officials, including Kofi Bonner, a key economic advisor who worked in the Mayor's Office of Economic Development at the time.

All were very supportive of the idea, Meriweather said.

(Silbert, however, claims she doesn't even recall meeting with Meriweather.)

The Insider

Long before he went to port officials, Meriweather discussed the idea with one of the few well-connected city leaders he knew: former police inspector Gilford.

Their first discussion occurred one morning shortly after the November 1995 general election, when Brown was clearly on his way to becoming the next mayor of San Francisco.

Gilford and Meriweather were in a group called Black Men of Action, which met regularly at the Southeast Community College to discuss ways to empower black youth, among other goals.

Gilford took Meriweather outside of the building to discuss the latter's plan. According to Meriweather, Gilford said that it was a fine idea, but that Meriweather had to come up with $60,000 in order to get support from "the boss."

"[Gilford] told me he had talked to [Brown] about the idea," Meriweather said. Gilford then told him, "Sixty thousand dollars and I can assure you'll get [his] blessings," Meriweather recalls.

There was no doubt in Meriweather's mind that "the boss" in question was Brown. Although Frank Jordan was still mayor and Gilford was a deputy mayor in the Jordan administration, Gilford had declared allegiance to Brown and was speaking frequently to the soon-to-be mayor.

Meriweather asked Gilford about the legality of paying $60,000 to win the favor of the man who would become the city's top elected official. Gilford told him that right or wrong wasn't the point. The point was "to get the wheels turning," he said, assuring Meriweather that the payment could not be traced.

"There are all sorts of accounts offshore," Meriweather recalls Gilford saying.

A highly decorated 18-year veteran of the San Francisco Police Department and one of the first two African Americans to serve on the department's homicide squad, Gilford met Brown at San Francisco State University when they were students there, and he had been a friend of Brown's for nearly 50 years. He was a consummate city hall insider, having served as executive director of the Mayor's Council on Criminal Justice under George Moscone, as deputy mayor for Dianne Feinstein, and as deputy mayor for former mayor Art Agnos, as well as Jordan.

Once Brown won the runoff in December 1995, Gilford began serving as a close confidant to him, as a member of Brown's transition team and a member of the mayor's brain trust. Brown rewarded Gilford's friendship and loyalty by appointing him to the Recreation and Park Commission in March 1997. Gilford was instrumental in helping Kimiko Burton-Cruz, daughter of state senator Burton, revive the Mayor's Office of Criminal Justice.

Gilford shared 49ers tickets with Brown, who visited Gilford just hours before he died of complications from diabetes.

In 1996 Gilford told a local newspaper that he had telephone conversations with Brown almost daily. "The relationship is such that things we discuss I won't talk about," Gilford told the San Francisco Examiner.

Gilford was also a close friend of Charlie Walker, a Bayview business-person and Brown buddy whose activities are currently the subject of a wide-ranging federal investigation into the city's minority contracting practices that recently resulted in a criminal indictment of a city official and three other individuals.

At one point Gilford told Meriweather to go to Walker to find the money, Meriweather says.

Meriweather believes Gilford wanted to see the port project happen to employ young people – not for personal gain. Gilford made it clear that the money was not a consulting fee for him. "Look at my house. Look at my cars. Do I look like I need any money?" Meriweather recalls Gilford saying.

Pressure to Pay Up

Between November 1995 and March 1998, Meriweather continued to meet periodically with Gilford, who consistently stressed that the $60,000 was needed in cash and that the payment was necessary to get the project moving. Cabellon and others in the group said they were uncomfortable with this demand, and they decided to handle it in their documents by calling the payment a "consulting fee" – even though Gilford made it clear the money was not for him.

"In order to substantiate the release of that funding – if the [backer] was to ask us what it was for, we had to substantiate that, so I suggested calling it a political consulting fee," Cabellon said. "Even though it was not."

Both Cabellon and Meriweather describe the $60,000 as a "payoff." They say they understood it to be a bribe.

One of the meetings took place at Gilford's house not long after Brown had been elected. Meriweather and Cabellon met in Gilford's bedroom. The mayor had popped into the gathering at the house but did not go into Gilford's bedroom. Cabellon and Meriweather both said in interviews that Gilford explained that $60,000 in cash was necessary for the project to go forward. They told us that Gilford did not say directly who would receive the money, but did specify that it would not be for him. Meriweather and Cabellon said it was clearly not a deposit for the project.

Cabellon said his impression was that it was for "higher-ups."

Environmental activist Ron Frazier, whom Meriweather had brought into the group, remembers hearing Gilford discuss the payment on another occasion. "You better hurry up or other people will take away the opportunity," Frazier recalls Gilford saying to Meriweather. Gilford chided Meriweather for not having produced the cash yet.

"[Gilford] said it would go to someone who could help process this through," Cabellon said. "This was going to be the catalyst, and it was stressed that cash was needed. In return, we would get assistance from someone with the power to circumvent the process."

"We were negotiating back and forth on this," he added. "Cash that large is hard to substantiate. There was more than one meeting on this. And there were telephone calls."

"My biggest concern was that [the demand for cash] was not going to stop there," he said. "Greed comes in."

Frazier said Gilford's demand discouraged him from becoming involved in the project.

Cabellon said ECCI members had thought about borrowing the money or going to other sources, but dragged their feet because they felt so uncomfortable about it.

"It's a payoff," Cabellon said. "That's how I looked at it. It was greasing the pump, so to speak, to circumvent the regular bidding process."

Gilford spoke with Meriweather about the need for the cash numerous times in meetings at Gilford's home and once in his office at City Hall – even up until his death. When Gilford was in the hospital in early 1998 after having his leg amputated owing to a diabetes relapse, he scolded Meriweather for not coming up with the money. "People are waiting for you," Meriweather says Gilford told him.

According to Meriweather, Gilford suggested that his friend Walker would have no problem coming up with the money. "If this was Charlie Walker's [project], he wouldn't walk in here with no money," Meriweather recalls Gilford saying. "It would have been done by now. Here I am with my leg cut off. But I can still lift one finger, make a call, and get the money. And you're telling me you can't come up with sixty thousand dollars. What the hell is wrong with you?"

Gilford suggested to Meriweather that he approach Walker for the money. But Meriweather did not want to deal with Walker, having gotten to know him somewhat during the 49ers' 1997 campaign for a new stadium. "Walker asked me if he could participate. And I said no. He told me he had some idea of how to get fifty thousand dollars from [former 49ers owner] Eddie DeBartolo. He said he would 'be the heavy,' but I was not interested," Meriweather told us.

Walker had no comment for this story.

On May 28, 1998, shortly after Gilford's death, the ECCI group met with Brown. According to two sources present at the meeting, Brown told them they needed to show they had "the wherewithal, the vehicle" to do the project and "get exclusivity."

The Competition

The port of San Francisco formally published a request for proposals to develop Pier 30-32 in June 1999. By then Meriweather's plan was effectively dead – without the inside connections Gilford had promised, he was unable to find anyone willing to help finance it.

By October two big development groups had submitted bids: a consortium called the San Francisco Cruise Terminal Inc. and a developer named LCOR.

LCOR, a Pennsylvania-based development company, offered Meriweather a piece of the project in late 1999. His job would be doing what he had already been doing: talking to community and business groups. Meriweather joined the team.

On Jan. 11, 2000, Port of San Francisco staff and a majority of commissioners agreed to give the well-connected SFCT the right to negotiate development of the Bryant Street Pier and James R. Herman International Cruise Terminal.

The team sports an intriguing lineup of heavy hitters with ties to the shipping industry in the Far East. Besides Lend Lease, a development and financing company headquartered in Australia, which holds 50 percent of the interest in SFCT, the team includes Whitney Cressman, a San Francisco commercial real estate firm, which has an 8.5 percent interest and will handle the leasing. The PSA Corporation, which was formed from the Port of Singapore Authority and is wholly owned by the government of Singapore, has roughly 20 percent interest in SFCT and will operate the cruise terminal.

About 20 percent interest is held by Chinese Maritime Transport, a group that's supposed to help market San Francisco's cruise industry. Port documents identify CMT as a subsidiary of CMT-Associated Group, an international maritime shipping company worth more than $200 million, founded by financier John Peng, the brother-in-law of a high ranking Hong Kong official.

"CMT itself is one of the few companies permitted to engage in direct cross-straight shipping between Taiwan and mainland China," SFCT's proposal states. In the summer of 1999 the group also tapped the Alfred Williams Consultancy (see "With Friends Like These...," at bottom) to handle "public relations and community outreach."

Using political connections, P.R. savvy, and on-the-ground organizing, the group pushed hard to sew up port staff and neighborhood support.

Sources close to the port say state senator Burton made sure the commissioners "fell into place." He called many of them requesting breakfast meetings to discuss the project, one source said. And several sources at and close to the port said Burton influenced the selection process.

Numerous sources close to the port and involved in the proceedings told the Bay Guardian that SFCT's bid was given favorable treatment from the port for political reasons.

"This was an inside kind of deal," one source who was approached by Burton said.

Burton did not return two Bay Guardian phone calls asking him to explain his involvement in the Pier 30-32 project.

The Bay Guardian called the four commissioners who voted for SFCT. Only Denise McCarthy could be reached, and she said she was not aware of any behind-the-scenes politicking. Pius Lee and Michael Hardeman did not return calls. Kimberly Brandon did, but when we called the number she gave us, we were told she no longer worked there.

Among the people who played a key role for SFCT was longtime city hall lobbyist Marcia Smolens. SFCT paid her at least $30,000 to push for the project, Ethics Commission records show. Burton has strong, longstanding ties to Smolens. From 1991 to 1999 Burton provided legal services to Smolens’ firm, HMS Associates, billing $10,000 or more annually, according to documents from the Fair Political Practices Commission.

Smolens did not return a Bay Guardian phone message asking if she requested Burton's help in pushing the project.

Asked if Burton or Smolens had contacted port staff, port planning and development director Osmundson said, "Not to my recollection." But, he noted, "We were aware Marcia Smolens was representing the developer."

Osmundson denies that support for SFCT from Burton, Smolens, Delancey Street, and the community swayed the port staff in its evaluation of the proposals. "We are extremely careful about what we put in these reports," he said. "We try to get the facts down from the developer's own perspective."

At the Nov. 17, 1999 Port Commission meeting (during which both teams presented their proposals), according to the minutes, Alfred Williams said that "over the past several months, the [SFCT] team held dozens of meetings with stakeholders and other parties concerning the project."

Indeed, several members of a key neighborhood group, the Rincon Point-South Beach Citizens Advisory Committee (CAC), confirm that SFCT representatives contacted and met with them frequently. (The CAC advises the port and the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency on development matters in South Beach).

"Every single community group was lined up, because they went out and sold it to the community," port commissioner Brian McWilliams, the sole commissioner to vote for LCOR, told us. "They did an effective P.R. blitz by hiring people who are good at that. Marcia Smolens does a good job."

The support of the influential Delancey Street Foundation, which is headquartered near the site, was a significant factor in SFCT's winning the right to negotiate, port sources say. Delancey Street director Silbert turned out both Nov. 17 and Jan. 11 for Port Commission meetings and gushed support for the proposal.

"They scaled the project down because of neighbors' responses," the Nov. 17 minutes quote Silbert as saying.

In an interview with the Bay Guardian, Silbert, who is friendly with Burton and Smolens, said she was unaware of any political juice behind the project.

"I really believe the process was without a lot of political interference and that [port commissioners] picked it honestly on the points that they said they were going to pick it on," Silbert said.

"My main concern, since this was the first big [port] development down here, and we stare at that pier and our restaurant depends on it, was that the [developer] be responsive to the neighborhood. And they [SFCT] were."

LCOR, too, was ready to address community concerns but did not get cozy with the neighborhood as early as SFCT did. The developer proposed creating several community advisory boards to provide input on design and environmental, traffic, safety, and waterfront access issues. And, like SFCT, LCOR presented its project to the Citizens Advisory Committee.

LCOR's chief failure, it seems, was that it didn't hire a high-powered city hall lobbyist. On that point, the developer miscalculated.

Thanks in part to SFCT's outreach strategy, community organizations near the site overwhelmingly endorsed the team's proposal. The minutes of the port's Nov. 17 meeting show a parade of support from neighborhood groups for SFCT. They were pleased that SFCT had agreed to scale down the hotel and retail area. They liked SFCT's proposal to turn the south berth into a lagoon for recreational activities that would provide on open view of the bay from the shoreline. In letters, public comments, and interviews with the Bay Guardian, they stressed that SFCT members were the first to discuss the project with them.

But now it appears that the elegant design the community liked so much may not be viable. Sources close to the port say there are problems with the plan that may not pass regulatory muster and could force changes.

"There's something about this process that is, I don't want to say dishonest, but we went through this whole exercise – all those drawings – all of that was just to negotiate," McWilliams said. "All of that was about who gets to sit down and talk. People don't understand that. They see a picture, and they think that that's what they're going to get, even though it may have nothing to do with what you get in the end."

Anne Cook, the port's manager of waterfront development, says that while many issues remain to be worked out with environmental and other agencies, she does not foresee substantial changes – though she admits she cannot guarantee that. The Bay Conservation and Development Commission (a port watchdog agency) and the port are still working out an agreement on waterfront development that will affect the project. Issues up for debate include dredging and parking. BCDC prefers little or no parking on port piers. The SFCT proposal places most of the parking on the pier – one of the ideas neighborhood groups liked.

The Wrong Project

Despite port officials' assurances that they conducted a careful, merit-based review of LCOR and SFCR, a Bay Guardian review of more than 1,000 pages of port records shows serious unresolved questions about whether the port – by its own criteria – chose the best pier project.

The documents reveal that the LCOR proposal was much closer to what the port had requested: LCOR's plans were more practical and promised more guaranteed revenue to the port. The SFCT proposal, while attractive, may not allow for San Francisco to become a player in the cruise ship industry, which is what the port had wanted, according to port reports written before the request for proposals was released. In addition, the SFCT proposal will require dredging of toxic sediments, which would have to be hauled inland, at considerable expense, to a secure landfill.

"Dredging is a big, big deal," Jennifer Clary, waterfront chair of the environmental group San Francisco Tomorrow, said. "That's when contaminants get stirred up."

SFCT had no comment.

Additionally, SFCT's final proposal to the port contained what appear to be serious financial inaccuracies.

At the Jan. 11, 2000, meeting, John Infantino, LCOR's vice president, pointed out a multimillion-dollar discrepancy between the two projects. The problem was only addressed after he raised the issue in a Jan. 10 letter to the port. In an interview with the Bay Guardian, Infantino said the issues raised were never resolved to his satisfaction.

Perhaps most puzzling about the port staff's decision to recommend SFCT is that LCOR was offering more revenue in "guaranteed" rent (money that is guaranteed whether the developer turns a profit or not).

In comparison, port officials have said they chose the more touristy and unpopular Malrite proposal for Pier 45 because the developer was offering more money.

According to port documents, LCOR was offering $2.4 million in annual, guaranteed rent to the port just during construction, while SFCT promised only $1 million. More than 60 percent of SFCT's rent package was based on speculative "participation" rent (a portion of the profits delivered, in this case, once the developer got a 12 percent return).

"LCOR had a better financial package with more money going to the city," Richard Ow, an immigrant rights commissioner and longtime union member who followed the proceedings, said.

SFCT did offer the port more in participation rent, but port staff seemed to ignore that, under the LCOR proposal, the port would have collected far more revenue than it would under SFCT's plan.

Curiously, the port staff's Nov. 10, 1999 memo to commissioners did not accurately reflect a public-private partnership proposal that LCOR had made. The staff wrote that the annual rent during construction would be $1.9 million – not $2.4 million. It did not mention the $4.8 million in guaranteed rent after construction, and did not put a number on the participation rent. The staff also incorrectly identified LCOR's "home-run insurance" as just 25 percent of annual net operating income generated beyond income projections – instead of LCOR's promised 50 percent.

According to Cook, port staff did not spend as much time considering LCOR’s public-private option and acknowledged that some mistakes could have been made in the evaluation of that option.

SFCT's proposal contained a glaring financial omission: the team failed to include the cost of retrofitting Pier 30-32 for earthquake protections. The port's June 1999 request for proposals showed that a retrofit was necessary, stating that "a seismic upgrade will be required to meet current building code seismic requirements." The upshot was that SFCT's revenue projections appeared to be about $9 million higher than was accurate.

Port staff knew that SFCT had failed to include that cost, port documents show. A November 1999 staff report lists LCOR's project costs at $350 to $375 million and SFCT's at $268,254,895 – a figure which "does not include pier repair or reinforcement," the report notes.

But the matter was not resolved until Jan. 11, 2000, the day the commission was to choose a bidder. Though the staff had recognized the problem by Nov. 10, 1999, it apparently did not direct its consultant, Economic and Planning Systems (EPS), to take that into account when analyzing the two financial packages.

"We had caught [the issue] early on," Cook said. "It just didn't make it onto the tables. It was last minute."

In its Jan. 7, 2000 report, EPS noted that SFCT did not include the cost of pier improvements – but EPS did not adjust the revenue projections to reflect that until one day after Infantino raised the issue in his Jan. 10, 2000 letter.

Not only did LCOR include the cost of retrofitting the pier, the developer also provided a plan for how to do it. The group also offered to tear down Pier 34 to create space for a new park. According to the port's June 24, 1997 Waterfront Land Use Plan, that pier should be condemned and removed.

Design Flaws

One of the greatest oddities about the port's decision to negotiate with SFCT concerns design issues. LCOR's offer met the terms of the RFP. SFCT's did not.

SFCT's proposal failed to meet the RFP's requirement that the project include two 1,000-foot-long and 35-foot-deep berths "that require little or no dredging" so that the pier can handle two cruise ships docked simultaneously. The SFCT team proposal calls for one ship to dock in the north berth – a plan port staff considered not viable prior to issuing the RFP, documents show. "The north berth is not being considered as a viable option for berthing ships: preliminary testing indicates that sediment from the north berth, which is quite shallow, would require upland disposal which would exceed $5 million," a September 1998 report by Osmundson states.

At 11 to 13 feet deep, the north berth of Pier 30-32 would require extensive dredging to make it suitable for a cruise ship. And at 845 feet long, it's too short to handle more than half of the ships cruising in North American waters, according to LCOR's proposal. The port staff recognized the need for longer and wider berths for San Francisco's future terminal. "Cruise ships are getting longer, wider and taller…. [T]he next generation is expected to reach 1,030 feet in length," a Sept. 2, 1998 staff report states.

LCOR devoted a significant portion of its proposal to explaining the advantages of using the south berth, estimating that initial dredging of the north berth would cost $7 million.

Nonetheless, "SFCT was able to convince our maritime staff that the northern berth would satisfy our foreseeable needs," Osmundson said. Because SFCT’s plan uses the north berth, the south berth could be turned into a lagoon for waterfront recreation. This feature has given its proposal greater community appeal. Residents living near the pier would have clear views, since no cruise ship would dock there.

Certainly, SFCT's project has its pluses, and LCOR's has its downsides. With the Port of Singapore on board, SFCT brings more cruise terminal experience to the table, port officials say. Port staff and consultants criticized LCOR's retail tenants for being too upscale and tourist-oriented, rather than focused on providing services to the South Beach community.

But commissioner McWilliams, who is also the president of the international headquarters of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, says the LCOR plan was still better. "Clearly, from a longshoreman's point of view, they had the better proposal for a working pier," he said. "This was about a working dock and a maritime facility. From the point of view of what was a much more passenger-friendly terminal, they had the better proposal.... The maritime issue seems to have gotten lost in the process."

For Meriweather, who is still struggling to revive his proposal, "the process" was corrupted a long time ago, back when his stomach turned at the idea of hustling a $60,000 payoff just to get his development on the inside track. His project, though clearly preliminary, had high ideals that Meriweather once thought were shared by Willie Brown – those of marrying urban development with real economic opportunities for low-income African Americans.

During his campaign, Brown had told Black Men of Action that his election would open up opportunities for people of color.

"He said, 'You haven't had a mayor that understands your problems like I do,' " Meriweather said. "That's what made me think we could go and do something and make some jobs for the city.... We should have known better." ***

Bob Porterfield contributed to this story

Second Side Bar: With Friends Like These

As Ernie Meriweather initially sought support for his project, many potential backers seemed eager to help. But months later some of these same people turned up working for his competitor – and Meriweather says that parts of his idea went with them.

Among the strongest earlier supporters was Maurice James, a Black Men of Action member who Mayor Willie Brown once appointed to the California Council of Criminal Justice.

Meriweather’s proposal also drew the interest of Alfred Williams, a government relations consultant with strong community ties.

Williams told Meriweather he had a friend who developed properties and could find the money to finance the project. That friend was Ranny Parker, a consultant who had a role in the development of Yerba Buena Gardens.

“Parker had told us that he would be the ‘missing link’ for the financial source,” Albert Cabellon, one of Meriweather’s partners in ECCI, said. “He even told us to hold off on seeking other investors.”

Williams came to two meetings of ECCI, according to ECCI documents.

According to Meriweather, in 1998 James suggested that the nonprofit organization he ran, Morrisiana West, could come up with $2 million in seed money. James asked Cabellon to provide him with the group’s budget. Cabellon did so.

But in September 1998, Williams and Parker said they were no longer interested. Cabellon’s jaw “just dropped,” he said. “All that time they had been encouraging us and meeting with us. When they said they weren’t interested. I knew something was up.”

In October, 1998, James denied that he had ever offered start-up money. In a letter dated Oct. 7, 1998, Meriweather wrote to James: “I must admit surprise overtook me when you told me on Monday that you did not tell me you could take care of the predevelopment money. I distinctly remember you telling me that.”

After the RFP was released for the Byrant Street Pier Project on June 4, 1999, Meriweather said he was told by members of the port’s staff that Williams and Parker had joined a different team that had filed papers and deposited $100,000, which was required of all interested bidders.

Port documents show that Williams is now a community relations representative on SFCT’s proposal, and Parker is listed as the group’s hotel developer. James appears nowhere on the documents and has no visible role in the winning project.

On Nov. 17, 1999, Meriweather complained to port commissioners that his work product had been stolen, the meeting minutes show. He reiterated that complaint in a letter he sent to port commissioners and Brown shortly after the Nov. 17 port meeting.

“[Williams and Parker] then took ECCI’s plan to another developer, Lend Lease, before the issuance of the RFP, which gave SFCT, LLC an unfair time advantage,” he wrote. “If Lend Lease obtains the right to develop the Pier, they will be profiting by the use of ECCI’s misappropriated plans.”

“We had a two-level [cruise ship terminal] plan with a hotel, a garden, and a museum,” Cabellon said. “It was not a direct copy, but the ingredients were there.”

Parker and James did not return calls seeking comment. Williams told the Bay Guardian that he had heard of Meriweather’s allegations, but he insisted that “a fuller investigation would prove them not to be true.”

Lend Lease officials had no comment on the allegations.

-- Savannah Blackwell